”The question of whether or not raids and reprisals are resumed – and of who raids and who reprises – is not a matter of such dramatic import as the press here contends. During the two years of scraggly border warfare that preceded the Israelis’ decision to raise the ante last October [the invasion of Egypt], the ‘crimes of the fedayeen’ claimed considerably fewer victims in Israel than the Israelis bagged on the Egyptian side of the line. The score kept by the UN observers of the Egypt-Israel Mixed Armistice Commission shows that between Jan. 1, 1955 and Sept. 30, 1956 the Israelis killed 239 Egyptian soldiers and 91 civilians, while the Egyptians killed 42 Israeli soldiers and 24 civilians – a ration of just under 6 to 1 in the first category and of just under 4 to 1 in the second. The discrepancy is a measure not of comparative ill will but of comparative efficiency. As for the widely photographed peaceful Israeli settlers of Nahal Oz, who work their fields under the menacing shadow of the fedayeen-haunted Gaza ridge, they are members of a paramilitary farm colony planted there about six years ago to catch raiders. Border kibbutzim, or collective farms, like this one are an institution copied from the Roman coloniae of ex-soldiers, who received land and livestock as an inducement to settle at points on the imperial frontier where they could be of the most utility when war came. The young Israelis go to these kibbutzim straight from army service. It’s a good old-fashioned procedure that provides lightly fortified Stutzpunkte along the frontier at minimal expense, since the colonists grow their own vegetables and dig trenches in their recreation time; the czars planted belts of Cossack colonies along the Tatar and Polish borders for the same purpose. The kibbutzim at points where action seems most imminent are favored not only in equipment but in the allocation of farm machinery and livestock; they are like army units being beefed up for action. A young farmer I talked with at Nahal Oz while the Israelis still occupied Gaza said, half regretfully, ‘We’ve been making great progress here, but if the Egyptians don’t come back soon, the kibbutzim on the Syrian frontier will be getting the pick of everything.’ Recruiting for the more sheltered kibbutzim is falling away with the waning of the young Israelis romanticism about the land; the persisting attraction of the border establishments is the opportunity to protect the fatherland from attack. (The only genuine romantic enthusiasm in Israel now, it seems to an observer from outside, centers on the armed forces. The popular line is that the army won the victory and the government threw it away – or Eisenhower or Hammarskjold or the oil companies stole it away.) The Israelis are far better qualified than their opponents for an indefinite game of cowboys-and-Indians. It is highly unlikely that the country will bleed to death because of the measly ‘incidents’ that the local press is already trying to blow up, like the theft of 3,000 dollars’ worth of farm machinery, of an unspecified nature, from the Israeli-governed Bedouin tribe named Abu Grab (in this case, more grabbed against than grabbing).”

From the article ”Letter from Tel Aviv” by A.J. Liebling, The New Yorker, March 30, 1957

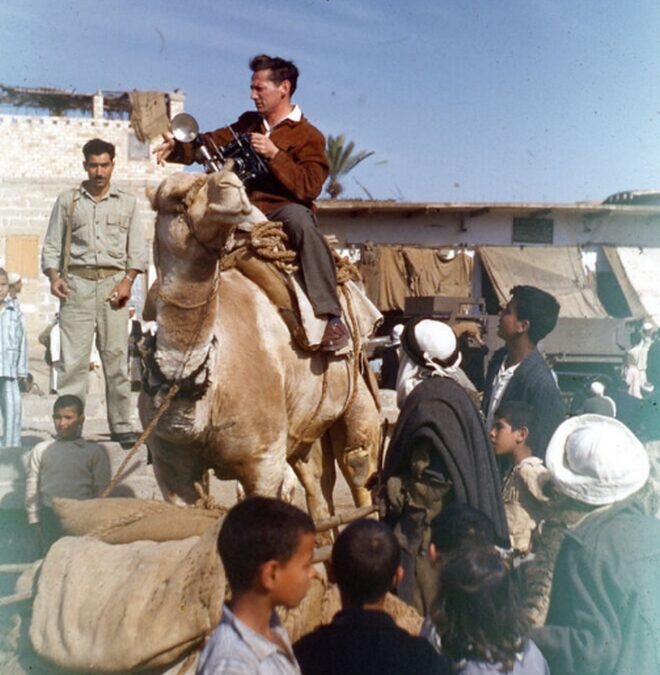

Caption: ”Taking a picture of a camel, 1956. The Moshe Marlin Levin Archive, the Meitar Collection, the Pritzker Family National Photography Collection at the National Library of Israel.”

Länk till The New Yorker här.